Mar 29, 2019

A new concern with proposed mega constellations of LEO satellites has emerged, and that is concern over satellites that are de-orbited and dropped into earth’s atmosphere at the end of their mission. This happens all the time, and the possibilities of damage or harm to people and property below have historically been negligible, but now companies such as SpaceX plan to launch thousands of new LEO satellites, and eventually, they will come down.

Having dead satellites fall back into earth orbit is a good thing. If they aren’t pulled out of orbit, they hang around like America’s second satellite Vanguard 1, launched in 1958 and still orbiting the earth as a piece of space junk. Since that time, Vanguard 1 has been joined by at least 20,000 pieces of space junk, and that’s just the ones that are larger than 10 cm in size. There are hundreds of thousands of smaller pieces of debris ranging from bolts to paint flecks, traveling at extremely high speeds, and capable of damaging or destroying other satellites, or even the International Space Station (ISS). The amount of space junk just grew by at least 270 pieces of debris, as India announced on March 28, 2019 that it had become the fourth country, joining the US, China and Russia to shoot down a satellite in space.

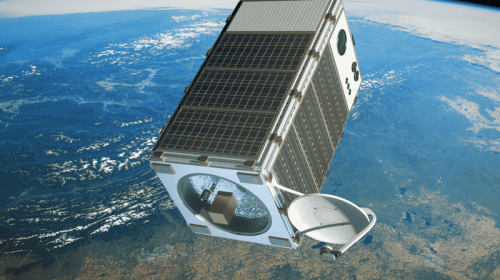

The space industry is a competitive affair, and OneWeb, who also has plans to launch their own mega-constellation of LEO satellites decided to bring to the FCC’s attention, concerns about SpaceX’s new constellation of satellites creating a hazard as they de-orbit in the future. Small CubeSats generally burn up completely on reentering the atmosphere, but fragments from larger satellites can survive. SpaceX’s Starlink satellites are about the size of a Tesla Model 3 and fragments from such large satellites can make it to earth. The likelihood of satellite debris causing a human casualty is about 1 in 10,000, but when you are talking about 12,000 satellites, the analysis says as many as 500,000 separate objects from Starlink satellites would reach the earth’s surface every six years, which significantly increases the chances for injury, death or damage.

The Starlink satellites have nine components that could potentially fall to earth including thruster parts, reaction wheels used for maneuvering and silicon carbide communications components such as mirrors for intersatellite laser links (which OneWeb does not support with their solution). Some of these would have enough energy to injure or kill, although just about any shelter would offer some protection. OneWeb filed a petition against SEH (Space Exploration Holdings, LLC – the holding company for the Starlink project), to deny or defer the deployment of the satellites. Along with concerns about Ku band interference issues, OneWeb raised the issue of the risk of death, injury or property damage as the thousands of SpaceX satellites eventually de-orbit as they are cycled out of service and replaced. The FCC asked SpaceX in February 2019 if they could direct the falling Starlinks to ocean areas far from human populations, and requested that SEH provide additional, detailed studies of casualty risks from its satellites.

SpaceX, never a company to react as anticipated, reported that it’s satellites could not reliably be directed to remote oceans, but said that it doesn’t matter any longer. A SpaceX lawyer reports “After extensive research and investment, SpaceX has now developed a system architecture that will be completely demisable.” While the first 75 Starlinks will include iron thruster and steel reaction wheel components, those built afterwards will “use components that will demise fully in the atmosphere.” Chances are these first 75 satellites are already in the construction process, which would back rumors that SpaceX could start launching Starlinks as early as May 2019. Just as OneWeb has launched its test satellites, so too has SpaceX with two prototypes launched early in 2018.

Starlink hasn’t commented yet on how it would deal with the silicon carbide mirrors that are presumably used for satellite to satellite laser links. This is a key advantage that SpaceX has over OneWeb, whose polar orbiting constellation uses a typical “bent-pipe” model, which means a satellite providing service must have line-of-sight to the remote site, and an earth station on the ground. With ISR or inter-satellite relay, Starlink satellites can pass traffic from one satellite to another to provide a remote site to earth station connection.

Thus far there are no details about how SpaceX intends to ensure that its satellites burn up in the atmosphere. Replacing iron, steel and titanium components with less resilient aluminum would significantly decrease the risk of pieces reaching earth, but it can’t be entirely ruled out. The risk level might drop significantly enough to not be an issue. In making its announcement, SpaceX changes the rules of the game. If it can guarantee that its satellites will completely burn up in the atmosphere, that puts the pressure on SpaceX rivals to come up with similar capabilities. If this capability exists, regulators will likely insist that all mega-constellations follow suit. There are many challenges to the deployment of these new LEO constellations, but the technical problems continue to be solved as they move forward.

Marketing and political problems, such as Russia denying OneWeb access to frequencies to provide services there, may prove to be more difficult to solve. The dangers of space becoming entirely unusable due to nations shooting down each other’s satellites, and creating a maelstrom of cascading destruction in space, (known as the Kessler Syndrome) cannot be overlooked.